The Arctic Frontline: How Melting Ice Is Redrawing Global Power Maps

The Arctic is emerging as the world’s newest geopolitical battleground — a region where melting ice is not only exposing natural resources but also unraveling long-standing agreements and alliances. Once considered a remote, icy expanse suitable only for exploration and environmental research, the Arctic is now central to major power rivalries, strategic claims, and international diplomacy.

Eight countries — Canada, Denmark (via Greenland), Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Russia, and the United States — comprise the Arctic 8 and form the core of the Arctic Council, which has been the leading body for governance and cooperation in the region. But climate change, shifting alliances, and rising energy demand have begun to erode this spirit of cooperation.

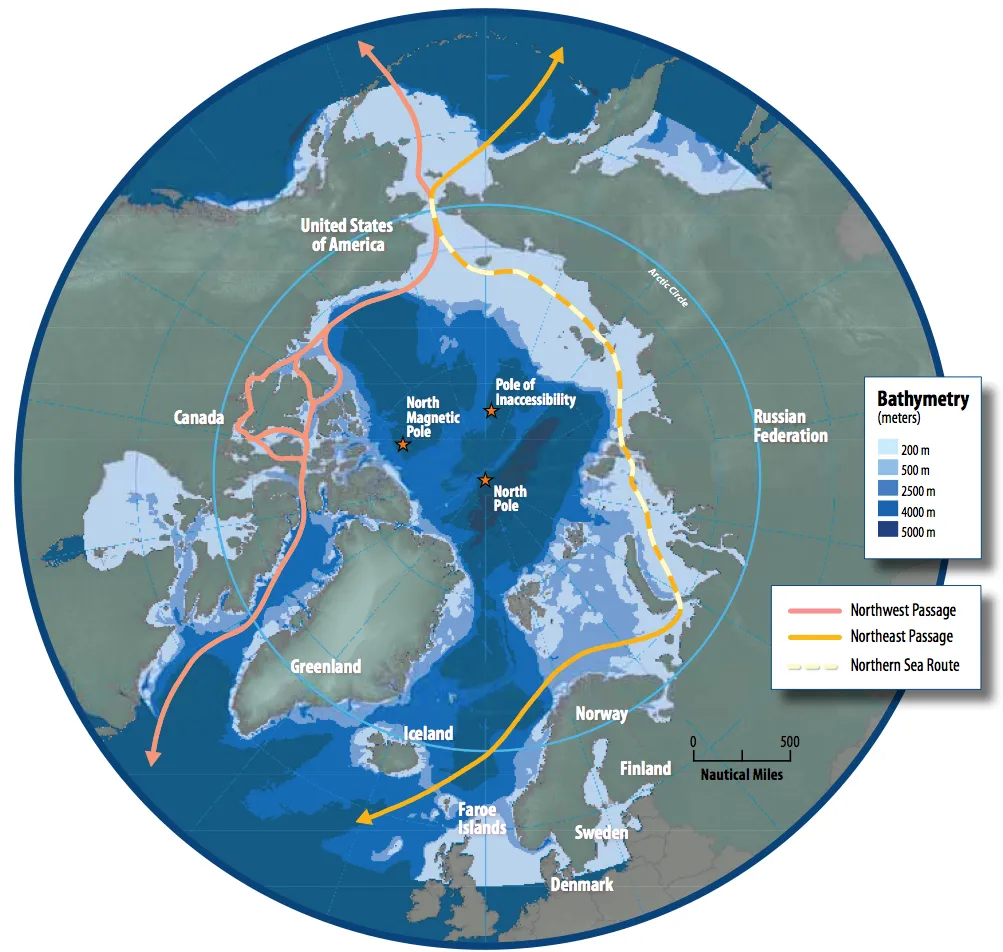

With the polar ice cap shrinking rapidly, previously inaccessible shipping routes like the Northern Sea Route (along Russia) and the Northwest Passage (through Canadian Arctic Archipelago) are now opening for commercial traffic. Beneath the ice, vast reserves of oil, gas, and minerals are drawing international attention, with overlapping claims from Russia, Canada, and Denmark over seabed regions such as the Lomonosov Ridge and the North Pole.

Russia has taken a militarized stance, reopening Cold War-era bases and asserting its control over the NSR. China, though not an Arctic state, declares itself a “near-Arctic” power and is expanding influence through research, shipping investment, and energy cooperation — especially with Russia. Meanwhile, NATO expansion into the Nordic region has increased Western presence, raising the risk of confrontation.

The legal framework of UNCLOS (United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea) is being tested, especially as the CLCS (Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf) reviews competing claims.

At stake is not just territory, but the future of Arctic governance, environmental protection, Indigenous rights, and global stability. This article explores the Arctic territorial conflict through its historical roots, current claims, rising tensions, and potential paths forward — offering a full view of the world’s coldest, yet hottest, new frontier.

The Arctic has long held strategic importance, dating back to the era of polar exploration and Cold War rivalry. For decades, its extreme conditions limited both access and attention, but beneath the surface, powerful geopolitical undercurrents were already forming.

During the Cold War, the Arctic served as a silent, militarized buffer zone between the United States and the Soviet Union. Nuclear-armed submarines patrolled under the ice, while long-range bombers flew over the polar route, leading to the deployment of a vast network of early-warning radars and airbases in the Far North — including NORAD and the DEW Line. While direct confrontations were rare, the region was heavily surveilled and maintained as a critical zone for strategic deterrence.

Despite this militarization, the Arctic remained legally ambiguous for much of the 20th century. That began to change with the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Although UNCLOS was not specifically designed for polar regions, it soon became the cornerstone for Arctic governance. It established rules for territorial waters, Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs), and allowed coastal states to claim an extended continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles — provided they submit scientific evidence to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS).

Over the years, UNCLOS became the legal framework through which Arctic states began to assert claims over subsea ridges, resource-rich zones, and potentially the North Pole itself. Countries like Russia, Canada, and Denmark (via Greenland) submitted overlapping claims — most notably over the Lomonosov Ridge, a submerged feature stretching across the central Arctic Ocean.

The creation of the Arctic Council in 1996 marked a diplomatic milestone. Comprising the eight Arctic states (Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and the United States), the Council focused on environmental protection, scientific cooperation, and sustainable development. It deliberately avoided military issues to maintain neutrality. For a time, this helped preserve a cooperative tone, supported further by the Ilulissat Declaration of 2008, in which the five coastal states reaffirmed that UNCLOS — not a new Arctic treaty — would be used to settle all maritime claims.

During this period, the Arctic was often described by diplomats as a zone of “High North, Low Tension.” Even symbolic disputes, such as the long-standing “Whisky War” between Denmark and Canada over Hans Island, were resolved peacefully. In 2010, Russia and Norway resolved a 40-year maritime boundary dispute in the Barents Sea through negotiation — reinforcing hopes that diplomacy would continue to define Arctic politics.

However, as Arctic ice continued to retreat at an unprecedented pace — driven by global warming — the region's geostrategic and economic value rose sharply. This has led to renewed military interest, shifting alliances, and assertive claims, shaking the cooperative foundation that had defined Arctic diplomacy for two decades.

Military Power and Strategic Posturing in the Arctic

As climate change unlocks the Arctic’s geographic accessibility, it is simultaneously turning the region into a new frontier for military posturing and strategic dominance. Among all Arctic states, Russia has been the most aggressive in asserting its defense interests. It has reopened over 50 Soviet-era military bases, stationed advanced missile systems across the Arctic coastline, and built a string of airstrips, radar systems, and Arctic brigades to secure the Northern Sea Route (NSR) — a shipping lane it considers sovereign territory.

Russia’s Northern Fleet, headquartered on the Kola Peninsula, remains the most powerful naval presence in the region, including nuclear submarines, long-range bombers, and ice-class warships. In recent years, it has conducted frequent drills and military exercises in Arctic waters, testing hypersonic missiles, anti-ship systems, and under-ice maneuvers, reinforcing the Arctic as a critical component of its defense and deterrence architecture.

The symbolic act of planting a Russian flag on the seabed at the North Pole in 2007 was more than a publicity stunt — it was a strategic message to the world about Moscow's ambitions. In 2023, the CLCS issued partial validation of Russia's extended continental shelf claim, adding pressure on Canada and Denmark, whose own claims to overlapping seabed areas (like the Lomonosov Ridge) remain under review.

In response, NATO has expanded its Arctic focus. With Finland and Sweden joining the alliance, NATO now includes seven of the eight Arctic Council members — leaving Russia increasingly isolated. Military exercises such as Cold Response, Trident Juncture, and Arctic Forge have significantly grown in scale and frequency, emphasizing Arctic defense readiness, cold-weather warfare, and air-sea operations in high-latitude environments.

The United States has also increased investments in Arctic defense infrastructure. The U.S. Coast Guard is developing new icebreaker vessels, while the Pentagon has designated the Arctic as a theater of strategic competition, especially with Russia and China. Surveillance capabilities have been upgraded, and strategic bombers are now regularly deployed to Greenland, Iceland, and Alaska as part of rotational missions.

Meanwhile, China, though not an Arctic state, is gradually asserting itself as a “near-Arctic” power. It has launched Arctic scientific expeditions, constructed ice-capable research vessels, and is investing in dual-use infrastructure projects in Greenland and Russian Arctic ports. Its 2018 Arctic Policy White Paper described the region as part of the Polar Silk Road, integrated into its larger Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

The combination of militarized infrastructure, exclusive interpretations of navigation rights, and expanding alliances has increased the risk of miscalculation. The lack of dialogue — especially after Russia’s suspension from Arctic Council working groups post-Ukraine — means that incidents like airspace violations, submarine tracking, or close naval encounters could escalate quickly.

The Arctic is thus shifting from a zone of scientific cooperation to a flashpoint of strategic deterrence — one where symbolic moves carry heavy consequences, and power projection often replaces diplomacy.

The Resource Rush and Climate Risk Paradox

As Arctic ice melts, it is revealing a vast, resource-rich region that has sparked intensified international interest and legal rivalry. The Arctic holds an estimated 13% of the world’s undiscovered oil and 30% of its untapped natural gas, primarily located in areas overlapping with competing maritime claims. Beneath the thinning ice lie not only hydrocarbons, but also rare earth minerals, uranium, and critical metals vital for clean energy transitions and defense technologies.

These stakes have pushed Arctic coastal states — especially Russia, Canada, and Denmark (via Greenland) — into a heated race to secure rights over the seabed. Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), countries can claim an Extended Continental Shelf (ECS) beyond their 200-nautical-mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) if they can scientifically prove geological continuity.

The most contested area is the Lomonosov Ridge, which stretches beneath the Arctic Ocean. All three countries — Russia, Canada, and Denmark — have submitted overlapping evidence to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS), each arguing that the ridge is a natural extension of their continental shelf. While CLCS may issue scientific recommendations, it does not resolve disputes, meaning multiple claims could be approved simultaneously, requiring diplomatic negotiations or arbitration.

Russia’s 2023 success in getting a partial recommendation from CLCS for its Arctic claim has increased friction, especially since parts of that claim directly overlap with Canadian and Danish submissions. Canada and Denmark have already stated they will not withdraw their claims, setting the stage for complex diplomacy — or potential escalation.

Meanwhile, climate change — the very force enabling this resource rush — is causing severe damage. The Arctic is warming four times faster than the global average. Thawing permafrost is releasing methane, melting glaciers are raising sea levels, and black carbon emissions from increased shipping are darkening ice surfaces, accelerating melt. The 2016 Norilsk diesel spill, caused by thawed ground beneath a storage tank, highlighted the disaster risk of industrial expansion in fragile permafrost zones.

New shipping routes like the Northern Sea Route (NSR) and Northwest Passage (NWP) are shortening global trade distances dramatically. But these routes remain legally contested and environmentally sensitive. Russia claims control over the NSR, requiring foreign vessels to seek permission and carry Russian pilots — a claim challenged by the U.S. and EU under UNCLOS's transit freedom clauses.

Despite the existence of the Polar Code (a maritime safety framework adopted by the International Maritime Organization), enforcement in remote Arctic waters is weak. With limited infrastructure for search and rescue, oil spill response, and environmental monitoring, a large-scale shipping accident or leak could be catastrophic — with lasting effects across Arctic ecosystems and Indigenous communities.

As interest in Arctic resources grows, tensions are emerging not only among states but also between economic development and environmental preservation. The European Union, for example, has called for a moratorium on new Arctic oil and gas exploration, while countries like Greenland see natural resource extraction as a path to economic independence and future sovereignty.

This resource and legal scramble raises key questions: Can Arctic claims be resolved without conflict? Will UNCLOS hold firm amid geopolitical rivalries? And is it even possible to sustainably extract Arctic resources in a rapidly warming world?

Role of Non-Arctic States & Indigenous Voices

While the Arctic has traditionally been governed by the Arctic 8 — Canada, Denmark (via Greenland), Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Russia, and the United States — the growing strategic and economic significance of the region has attracted the attention of non-Arctic states, reshaping the geopolitical landscape.

China is leading this shift. Though not geographically Arctic, China declared itself a "near-Arctic state" in 2018 and released its first official Arctic policy in the same year. It envisions a "Polar Silk Road", integrated into its broader Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). China has built ice-capable research vessels, invested in Arctic energy projects (notably Russia’s Yamal LNG), and funded infrastructure across the Northern Sea Route. Through scientific diplomacy, port development, and satellite monitoring, China is steadily increasing its influence, all while maintaining observer status in the Arctic Council.

India, too, is stepping into Arctic affairs. With growing global environmental responsibilities and commercial interests, India released its first Arctic policy in 2022, outlining strategic, scientific, and economic objectives. It operates a research station in Svalbard and participates in Arctic Council scientific activities. While India does not assert direct strategic claims, it is positioning itself as a responsible stakeholder in climate monitoring and future trade.

The European Union, although not an Arctic power, plays a major policy role. It has advocated for the halt of Arctic fossil fuel development, citing environmental protection and sustainability. Its influence is channelled through funding scientific missions, monitoring emissions, and shaping global Arctic discourse, even as some Arctic states — especially those dependent on extractive industries — resist such directives.

Japan and South Korea, both Arctic Council observers, are also investing in ice-class shipping technology, maritime safety, and Arctic scientific collaboration. Their involvement in Arctic shipping and LNG infrastructure shows how East Asia views the Arctic as a key component of future supply chains.

Alongside these emerging players are the often-overlooked Indigenous Arctic communities — including the Inuit, Sámi, Chukchi, and Nenets peoples — who have lived in the region for millennia. They are now asserting their voices not just as cultural stewards, but as active stakeholders in policy debates.

Organizations like the Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) and Saami Council are pushing for greater inclusion in decision-making at both national and international levels. These groups emphasize that Arctic development should prioritize environmental protection, community consultation, and long-term sustainability, rather than just geopolitical or commercial gain.

The regional dynamic is no longer Arctic vs. Arctic — it’s Arctic states vs. a growing ring of interested global actors, each with their own goals, values, and degrees of legitimacy. At the heart of this transformation lies the question: Who truly has the right to shape the Arctic's future?

"“The Arctic is where climate change collides with great-power politics — melting old boundaries while drawing new ones.”

— NATO Parliamentary Assembly, Renavigating the Melting Arctic (2025)"

The Arctic of the 2030s — What Comes Next?

By 2035, the Arctic may be seasonally ice-free — unlocking central routes, exposing seabed resources, and heightening international friction. Whether that future becomes cooperative or confrontational depends on how the world chooses to respond now.

Optimistically, we may see negotiated settlements on seabed claims, renewed Arctic Council cooperation, and shared infrastructure development — including fiber optic cables, search-and-rescue coordination, and marine protected areas.

Pessimistically, we face hardened blocs: Russia asserting dominance over the NSR, NATO reinforcing its Arctic periphery, and China leveraging scientific platforms for strategic advantage. In this future, the Arctic becomes a theater of deterrence and denial.

Greenland could emerge as an independent state, and the U.S. may finally ratify UNCLOS to strengthen its legal claims. Indigenous voices may gain more legal ground or be pushed aside, depending on how inclusive future frameworks become.

The question now is not just who will “win” the Arctic, but whether the region can be governed wisely and cooperatively in an era of multipolar uncertainty. Will the Arctic remain a zone of peaceful dialogue, or will it fracture into spheres of influence backed by military muscle? Will the lessons of Hans Island and the Ilulissat Declaration guide future actions, or will power politics eclipse restraint?

The next decade will answer these questions. And the choices made by Arctic and non-Arctic states alike will determine whether the region remains a beacon of possibility — or becomes a casualty of the new Coldest War.

-

NATO Parliamentary Assembly. Renavigating the Melting Arctic: Strategic Interests and Emerging Risks, 2025.

-

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), 1982.

https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf -

European Commission. EU Arctic Policy Update, October 2021.

https://ec.europa.eu/environment/ arctic-policy-2021.pdf -

Ilulissat Declaration. Meeting of the Five Arctic Coastal States, 2008.

https://www.oceanlaw.org/downloads/arctic/Ilulissat_Declaration.pdf -

Arctic Council. About the Arctic Council, 2024.

https://www.arctic-council.org/about/ -

NASA Earth Observatory. Arctic Amplification and Climate Change, 2023.

https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/features/ArcticAmplification -

International Maritime Organization (IMO). The Polar Code: Regulations for Arctic Shipping, 2017.

-

The Arctic Institute. China’s Arctic Strategy Explained, 2022.

https://www.thearcticinstitute.org/chinas-arctic-strategy/ - Image Credit: Arctic Council Secretariat